What Financial Institutions Can Learn From Streaming TV Series

This WFH culture has not only exponentially grown our digital footprint – it has also shaped our ability to consume more digital content. Streaming TV services grew in leaps and bounds; just look at the numbers that Netflix reported: from 2019 to 2021 they acquired 222 million new subscribers. And while some of this growth could be chalked up to the popularity of streaming services, as well as the viral effect of our FOMO culture not wanting to miss out on that latest show – one thing is uber clear, the pandemic kept us all closer to home, therefore closer to our TVs.

I myself, for the first time in a very long career in IT, was stuck at home and not traveling, therefore when not confusing Sunday for Monday, I also tuned in to see what all of the fuss was about. My background is security, my role is head of marketing, and I am always astounded by our cultural response to a particular fad, topic or just our general ability to allow the sensationalization of something to drive a change in behavior. Even more astounding to me, is when I can draw comparisons between my work life and real life – and the past few months have certainly created that for me.

Fraud is a part of my everyday work life, or more specifically educating the market on what Duality is doing to combat fraud via our data collaboration platform. (Now this is not a Duality pitch, but it is important to mention that our platform is not limited to fraud; it expands to enabling organizations to have the knowledge that technology can empower them to do more with their data, both privately and for the greater good). So like so many others who jumped on the streaming bandwagon, I sat through Inventing Anna, The Tinder Swindler, Bad Vegan, Dirty Money, the Great Hack, just to name a few – and realized they all had 3 things in common: they were predictable, they were preventable, and they heralded a need for evolving our ability to maintain privacy, while strategically tackling fraud.

For this blog in particular, I am zeroing in on financial institutions and the role they can take to ensure that the Anna Sorokins (aka Delvey) and Shimon Hayuts (aka Simon Leviev) of this world don’t become repeat offenders, or encourage others into risking a stint at the high-life, for a stint behind bars.

In fact, many of the headlines you are seeing today about this group of bad characters focus on the lies that were believed, versus how they were enabled to deceive. How could so many people not question the veracity of their tales and fall prey to their twisted reality? In a recent guest essay in the New York Times by Liz Scheier titled The Victims of Scammers Aren’t Stupid. They’re Human, she opens up about the fairytale life that her mother created for her, which in later years she learned was far from reality. Why are we so willing to believe the unbelievable? Is it that sometimes it is easier to believe the beguiled lie, then to challenge that feeling in your gut that is signaling, “hey you, something isn’t right here!” It’s my opinion that it’s human nature to want to trust; not to question, especially when you are feeling rewarded; and often we make the assumption that in this day and age of digital transparency, credit checks and approvals – their bank would know it’s a game of fraud. Well, not necessarily.

What Everyone Should Know About Finance and Privacy

You can blame the pseudo-friends for being gullible. However, nowadays, shouldn’t financial institutions be leveraging technology that is enabled to preserve privacy – especially data collaboration across borders – to better intersect these shady characters?

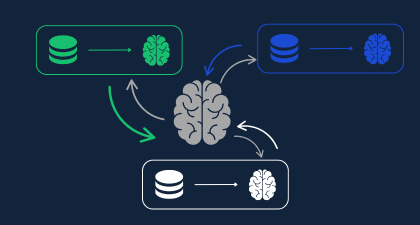

For years, financial institutions have been more engineered to solicit their own data to make qualified decisions versus the beneficial alternative of multisource, collaborative data sharing. When tackling data sharing, it’s important to understand it from the regulatory compliance perspective. It’s also important to understand the various forms of data that institutions must address and comply with: standard personal data vs.sensitive personal data. Standard personal data (also known as personally identifiable information, or PII) relates to information with a particular reference to an identifier, such as names, identification numbers, location data, and online identifiers, or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural, or social identity of that person. This also includes financial privacy that refers to the maintenance of confidentiality of customer information about transactions and finances. However, sensitive personal data refers to personal information that reveals racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs, trade-union membership; or data concerning health or sex life and sexual orientation; and genetic data or biometric data. Today, most organizations require stronger grounds to process personal sensitive data than required with standard data.

The finance industry is one of the primary holders of sensitive data, and many would agree that they have gone through one of the most significant digital transformations in the last decade. There was a visible paradigm shift in the way that banking was being conducted, as they slowly moved away from the ‘brick & mortar’ type of business to one that is continuously increasing their digital footprint – through the adoption of internet banking, on-the-go apps, and a more technology-driven digital experience. However, as much as their service infrastructure has matured, their knowledge of how to leverage technology to drive more insights from their data – while also maintaining its privacy, especially across multiple institutions – has not evolved. There are a number of factors that could be impacting this adoption latency – such as not having an internal data transformation owner responsible for employing data collaboration best practices; a predisposed fear of inadvertently oversharing data and losing a competitive edge or potential customers; and, ultimately, trying to abide with countless local, national and global regulations that make data sharing nearly impossible. When it comes to data privacy regulation, there rarely is a universal law applicable to all, and there often is a significant variation between data privacy regulation and enforcement harshness, which makes cross border data sharing burdensome. In other words, not only are the specifics of the data privacy laws variable, the consequences are too – and different countries enforce those laws to different degrees of seriousness. Ultimately, GDPR is the closest we have to a global privacy act at the moment, and that is limited only to participating EU member states.

How Innovation Impacts Privacy Transformation

So back to how these Netflix featured scams could have been predicted, prevented and privately preempted. Both Anna and Shimon presented fake personas, illegitimate financial records and varied forms of an unaccredited life. Retail establishments, travel services and a bevy of financial institutions opened their doors to their corruption and lies. If these multiple sources had the know-how to share information across their infrastructure and borders, enabled with best-practice modeling capabilities, there’s a good chance these scammers would have been stopped earlier in their litany of deceits. I am witnessing amazing progress on a daily basis in this regard, and I believe we owe it to our own evolution to encourage privacy preserving data sharing that promises to drive change for the masses and shape the very evolution of the data sharing landscape. Imagine for a moment the depth of information we can get from a simple health application which you subscribe to share your nutrition, workout, health regimen and even medications that are managed through it. Now imagine keeping your personal sensitive information private, yet sharing the remaining in a collaborative way. You could benefit from knowledge that is pooled from other users to optimize your workout, and learn that others on the same medication as you are sleeping less- these insights gained by using privacy preserving data collaboration could be life changing, even world changing.

In conclusion, institutions should not let regulations discourage them from driving value from their data and should instead lean into technologies that enable cross-institution, cross-border and privacy-preserved data sharing that will empower them to not only stop scammers but also help our greater economic state, and ultimately allow for a knowledge enabled better tomorrow.

There are other benefits to supporting the shift to improving how we globally collaborate on data. In fact, this past year McKinsey & Company released a discussion paper, Financial data unbound: The value of open data for individuals and institutions”, where they state, “Economies that embrace data sharing for finance could see Gross Domestic Product (GDP) gains of between 1 and 5 percent by 2030 with benefits flowing to consumers and financial institutions. More on this in an upcoming blog.

To learn more about what Duality and experts across law firms, leading banks and the FFIS Think Tank are doing to address the business potential and regulatory challenges associated with cross-border data sharing, watch our webinar below.